In this post you will read my scientific findings and personal experience in combating digestive illness. Around two-three years ago my health rapidly started to decline, and it was unclear why. I started to have problems eating without experiencing a lot of pain and other issues. I got sick much more. I was always tired, and there were various other unexplained symptoms. Together with my doctor I examined the problems and tried various medications and diets, and was sort of diagnosed with IBS which probably started with an infection followed by a series of antibiotics.

Around 7 months ago I reached the conclusion that the diet I was using to manage IBS gave me no quality of life, and the diagnosis was not an unsolvable problem. I concluded that I needed to spend more time myself understanding the problem and looking for solutions. In doing so, I learned that there are many people with digestive health issues: IBS, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, food allergies, bad smelling farts, you name it. I also learned there are very few people with valuable answers and there is a lot of nonsense to be found on the internet. This is one of those subjects where the gap between what the scientific community knows and what the rest of the world knows is very large. Unfortunately doctors also find themselves at a loss, as they often can’t help and have insufficient time to properly educate themselves on the subject. I therefore decided to write down my findings, largely based on scientific papers. I expect the majority of the information is correct, although it is probably incomplete to some degree.

Based on this information I have formed a ‘protocol’ for myself to firstly reduce complications and second to pursue recovery and elimination of the problems I face. I am nearly 5 months into this protocol and have achieved great reduction of complications, I expect these improvements to continue and my hope is to reach a state of more overall health stability and higher resilience. I am sharing this information with you as perhaps you will find some value in it as well.

Disclaimer: always consult your doctor before taking advice from anything on the internet or humans without a medical degree.

1. The digestive system

The start of tackling digestive health issues is understanding the digestive system. I have a background in bioprocess engineering, a field of engineering where chemical reactors are designed for anything from oil processing, to pharmaceutical manufacturing, to wastewater treatment, which is what I specialized in. Due to this background I tend to look at things from a process perspective. Looking at the human body, the heart is a pump, the brain a control system, nerves are sensors, and the digestive system is a fantastic and complicated biochemical system of multiple units.

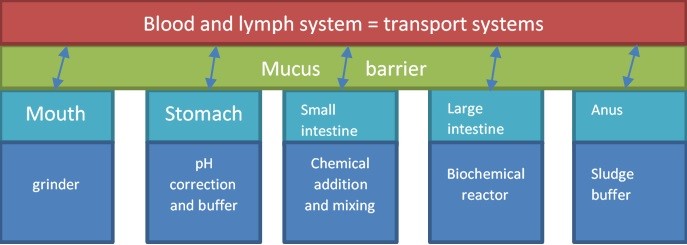

The main function of the digestive system is to take energy and nutrients out of the food we eat, deliver it to the blood system, from where it is transported throughout the body for various functions (brain, muscles, etc.). It does so by absorbing small molecules through a barrier and along the way (from the mouth to the anus) converting the food into small molecules that can be absorbed. Below a general process flow diagram of the human digestive system.

1.1 The mouth, stomach and small intestine

The mouth, stomach and small intestine have both the functions of absorption and conversion. First, to absorb small sugars and nutrients into the blood stream and second is to add digestive juices from the stomach, the pancreas, the liver and the intestine and convert the food into chyme, a fully mixed and pre-treated lump of macromolecules ready for digestion in the larger intestine. If they fail at either of those functions this can lead to problems downstream, where fermentation of the macromolecules takes place. If they fail to absorb smaller sugars these will pass on to the larger intestine and can lead to excessive gas production and unbalance in the microbiome. If they fail to mix and pre-treat the food, it can lead to problems with the completion of the fermentation of the macromolecules.

If you have problems in the large intestine it can be valuable to check if everything is “ok” in previous steps of the digestive process. Well-known problems of the stomach are the functioning of the muscle (a valve from a process perspective) at the end of the esophagus. If it does not close properly it will lead to acid reflux. Or a high concentration (infection) with helicobacter pylori, which settles in the stomach lining and can cause ulcers.

A known problem of the small intestine is lactose intolerance, which leads to fermentation of lactose in the larger intestine causing excessive gas. Another problem is gluten intolerance, which damages the lining of the smaller intestine leading to mall absorption of nutrients and other molecules, causing deficiencies and possibly disturbing the fermentation in the large intestine.

Basic check points to see if you have a problem here:

- Assess your oral health

- You can do a bit of massaging and pressing on your stomach and intestine. It should not be painful, and if it is something is off.

- You should not be taking anti-reflux medication on a regular basis.

- Your doctor can do testing. Blood analysis will show if you have any deficiencies or infections. They can also test for lactose intolerance, gluten intolerance, the absorption of sugar from your intestine into your blood and they can enter with a camera and take biopsies to analyze if the tissue is damaged.

1.2 The large intestine

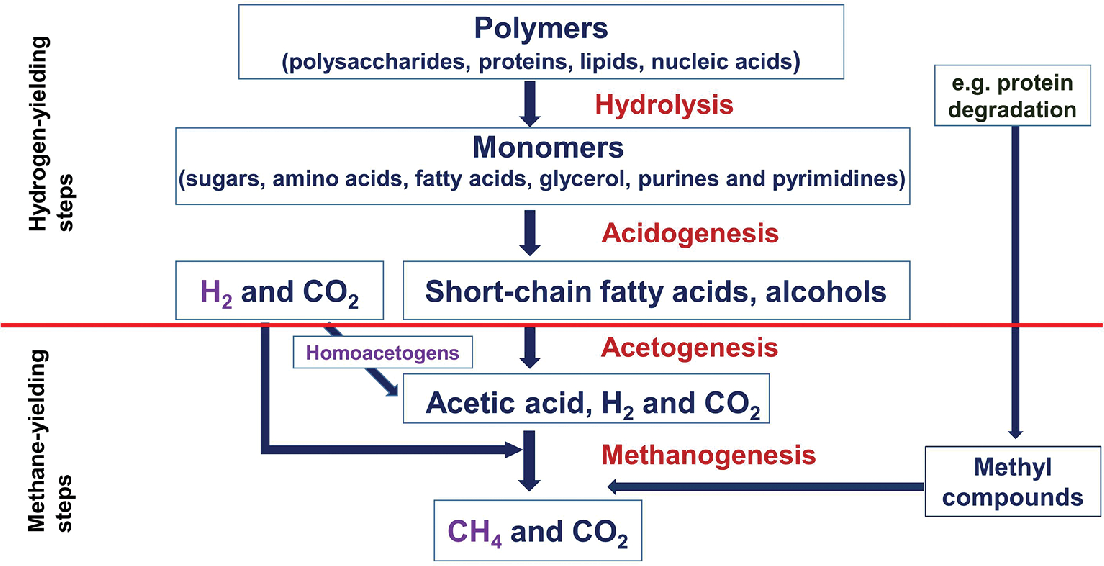

The large intestine is an anaerobic digestive bioreactor (Sonnenburg, 2004) where individual bacteria extract energy from molecules that serve as the electron acceptor of the fermentative reaction. Using the fermentation reaction an organic waste product is created that will serve as food for another category of bacteria. In this way the bacteria eat and stay alive, while converting large macromolecules to smaller molecules (short chain fatty acids) that will be absorbed through the barrier of the intestine and into the blood stream. The figure below shows a general scheme of anaerobic digestion. In the human intestine the short chain fatty acids will be absorbed through the barrier, acetate is metabolized in the hearth, brain and peripheral tissue (MacFarlane, 1997). The organic waste products, intermediate and final, can be dissolved into liquid or be gaseous (for example CO2, CH4, H2, H2S). Gas formation can be good, as it creates movement through the intestine, but can also be excessive and cause pain and bad smells. A disturbance in the microbiome (for example due to antibiotics or food poisoning) can result in different, and different concentrations, of the intermediates and end-products and cause pain and problems.

2. The barrier

On important characteristic of the digestive system is the boundary between the digestive system and the blood system. As the food we eat is dirty and covered in bacteria, mother nature has equipped the digestive system with tools to make sure those bacteria can’t enter the blood stream and make us severely ill. This has resulted in a triangular relationship of influence between the mucus barrier, the immune system and the microbiome. A disturbance in this relationship can cause problems and lead to long-term illness. Below these 3 pillars (microbiome, intestinal wall and mucus layer, and intestinal immune system) are explained individually, followed by their relationships.

2.1 The microbiome

Above I explained the general digestion that takes place in the large intestine. All these steps are executed by microbes, mostly bacteria. A general rule for communities of bacteria (or any living organism) they shape themselves to their environment. If you want to grow a certain type you must create conditions that will give them a competitive advantage, and if you want to get rid of a certain type you need to stop creating the conditions that give them the advantage. So far, all studies I have read naming specific species do not provide definite conclusions on which species are part of a healthy microbiome, and which are harmful. And many species seem beneficial until the concentration becomes too high, and they become harmful, expressing both mutualism and pathogenicity.

Personally I believe in an approach as set by environmental engineers: targeting a healthy ecosystem, focusing on the conditions for the slowest growing organism and looking at required functions in that ecosystem. This is already a challenge for GI microbiology (Zoetendal, 2015), and trustworthy information is limited at this time, but due to new techniques has started to develop in recent years. There are some interesting perspectives on the growth of the microbes as a community. It is though the majority of growth is in the form of a biofilm with interaction with the outer mucus layer, where the persistence of an organism depends on its ability to replicate faster than it can be shed by the mucus. Second, a part of the growth is connected to incoming food particles and part is unattached growth (MacFarlane, 1997; Probert, 2002). The only point of attention is that it has been indicated in several studies that initial colonization is very important, and microbiota does not generally make big changes during a life time. It is relatively stable in healthy individuals and unstable in individuals with IBD.

A high level of variability between individuals has been revealed at the species level, a more stable common pattern emerges at higher-level taxa. These predominantly include Firmicutes (Clostridia, Enterococcaceae, Lactobacillaceae and Lactococcus) and Bacteroidetes (including Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron, Bacteroides fragilis and Bacteroides ovatus). The remaining 10% belong to Proteobacteria, Fusobacteria, Actinobacteria, Verrucmicrobia, Sprirochaetes phyla and cyanobacteria (Hooper, 2010). It would indicate it is difficult to completely change your microbiota, but reaching a more stable situation, and shifting species, might be manageable.

There are various ways for seeding new bacteria to your intestine. Probiotics are a well-known and the right ones can be very helpful, downside is that the selection of microbes available if very limited. Fecal Matter Transplants (FMT) have started to gain popularity, but I do not have any practical experience with it (personally I think it’s too soon in its development and there are too many unknowns). With the “at home” version you don’t know what you get, you just know it is different than what you have. It can turn out good, but it also has risks. There are clinics that provide these treatment techniques, which have reported 30% immediate success, 30% change over time, and 30% unsuccessful (but these figures have since been removed from their website). Although I think there is potential for the future, these results are like what a randomizer would give. Personally, I find the financial investment and risks too large and view it as a last resort kind of solution.

Practical takeaways in supporting a healthy microbiome :

- To find out if the microbiome was part of my problem, I had my microbiome tested by different parties and found out certain species were present in very low concentrations compared with the norm.

- As my current best strategy is to approach the norm I did brief research on probiotics and started with Symprove.

- I am currently redirecting my diet to continue to feed these microbes to get them to stick around this time (with pre-biotics and possible early life nutrition), or if this fails to continue to use the probiotics.

- One of the conditions for reaching a more stable microbiota is food (pre-biotics), and that’s the easiest one to control, although it is debated how large this influence is. In terms of prebiotics I found via providers of microbiome testing the following foods were supportive for my microbiome:

- Apples, kiwi, pickles, mushrooms, sauerkraut (I ate a combination of these each morning as part of breakfast)

- In a step by step approach increase the amount of fiber, and select more variety of fiber

- More vegetables and fruit

- As much as possible, I eat a large variety of foods. This was the opposite of what I was doing before, where I stopped eating many products that were causing problems, which probably killed the last bit of bacteria that were able to digest them. Before I was doing the fodmap diet, which did not work for me, so I started to eat small quantities of specific products and started to increase them. For example from one mushroom in the morning up to 10 without problems. I do not eat things I have an allergic reaction to, more on this later.

- I also greatly reduced meat and fish consumption, and balanced protein intake to the minimum. One of the reasons is these products contain a lot of sulfur, and sulfur reducing bacteria have been linked to an inflammatory state of the gut (Jakobsson, 2014).

- No alcohol, I was unable to process alcohol and would have a 2-day hangover after half a glass of wine. Alcohol tolerance has become an indicator for me to see how well I am doing.

- Other factors influencing stable microbiota are the conditions of the intestine itself, mainly the mucus layer and the immune system. It will take time to balance these, and it’s an iterative process.

- Unless your immune system is severely compromised, don’t be too clean (but also don’t be an idiot).

- I got a hamster :-)

2.2 The intestinal wall and the mucus layer

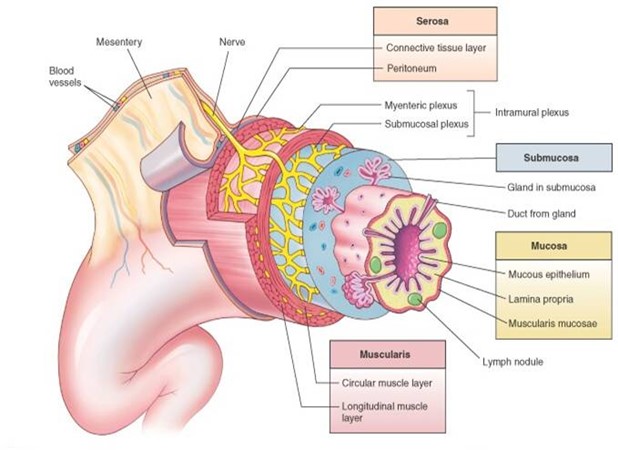

The intestinal wall is built up in several layers, one of which is the mucosa or mucus layers as displayed in the figure below.

Cross-section of a typical segment of the intestinal wall showing the four principal layers and associated structures: mucosa, submucosa, muscularis, and serosa. Although different areas of the GI tract specialize in function, the anatomy of the wall is similar in structure. (From Patton KT, Thibodeau GA: Anatomy & physiology, ed 8, St Louis, 2013, Mosby, p 863.)

The mechanical activity of the gastro-intestinal serves to store and propel chyme, and aids to extract fluids and electrolytes and stimulates the compacting of debris into feces. Mechanical strength of the bowel wall is determined by the submucosa and muscular layers. The serosa and mucosa have no significant strength. The mechanical stability is determined by the submucosa (Egorov, 2002). For the esophageal it has been indicated the mucosa may make an important contribution to the strength of the wall, and inflammation reduces its strength (Goyal, 1971). Overall it is indicated the mucosa/mucus layer has no significant impact on the mechanical movement, and this is predominantly determined by the muscles. However, it is also proposed that the bowel itself can become abnormally sensitive to stretching and contracting (inappropriate muscle/nerve activity) and be the cause of many post-infectious IBS symptoms. Specifically this could be explained by damage to nerve lining, eating, stress and emotions (muscle tension), and hormonal fluctuations (Kellow, 1995).

Practical takeaways:

- Evaluate portion sizes and change to eating more frequent, but smaller meals, to avoid putting too much pressure on the muscles and the wall and allowing time for digestion.

- Eat slower and chew more

- If digestion in general was too exhausting, I made it as easy as possible by minimize how much I ate and not overspending my energy. Your body is an energy balance, and at the moment you have a limit in how much you can take in. In periods where it was bad for me I partially went back to baby food so I could recover while keeping my body nourished.

- Stopped exercise. There was also a period where any exercise was too much as I just did not have the energy in my muscles, but at the time I felt I needed to push harder and work through it. As it did not make things better, and only seemed to make it worse, I quit exercising for a number of months until I found I had excessive energy in other muscles. This has been very positive and overall I have more energy and have been able to slowly pick things up again.

- Focus of muscle relaxation and tension release.

- Do deep breathing, this is both relaxing and provides some movement.

- Try massaging the intestine to aid digestion.

- I found peppermint/mint tea to be helpful with pain.

The mucus layers

Mucus is a semipermeable barrier that enables exchange of nutrients, water, gases, odorants, hormones and gametes while being impermeant to most bacteria and pathogens (Cone, 2008). Mucus protects most surfaces of the body, and plays a vital role in the protection of the eyes, nose, lungs, vagina and gastro-intestinal tract. Nearly 10 liter of mucus are secreted into the GI tract each day, of which most is digested and recycled. Mucus is continuously being secreted from the epithelium, which has a turn-over time from 3-6 days (Probert, 2002). The thickness of the mucus blanket is determined by the rate of secretion and the rate of degradation and shedding. Water with various compounds moves its way upstream through the mucus layer towards the epithelium for absorption, by which the mucus layer serves as a filter medium.

The effectiveness of this filtering process depends largely on the viscoelasticity (how gel-like or watery the mucus is), too thick will block transport and too thin will allow passage of possible harmful components. The regulation of the viscoelasticity is likely to be executed by the ionic environment and hydration of the mucus. The selectivity of the mucus layer is not only based on size-exclusion, but also the hydrophobic nature of the compounds, and in the case of bacterial penetration antibodies accumulate and entrap the pathogens.

Several studies (Schultsz, 1999; Johansson, 2014; Corazziari, 2009; McGuckin, 2009) have linked the penetration of bacteria into the (inner) mucus layer (there are some mixed messages about further penetration towards the epithelial layer, submucosa and deep tissue due to the difficulty in handling the tissue), with symptoms of Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC). Microbial invasion is unselective and non-specific, although spatial distribution is found to be shape dependent. The diseases are likely to occur in genetically predisposed individuals, how it is expressed is debatable. It may be in a reduced number of goblet cells, which synthesize mucin. However, penetration in monozygotic twins is less than 50% for CD and less than 20% in UC (McGuckin, 2009).

The diseases are expressed in combination with environmental and microbial exposure. It was indicated the quality of the mucus and not the thickness of the mucus layer is explanatory for penetration, and that microbial composition can affect the degree of inflammation. Moreover, a study (Jakobsson, 2014) tested the effect of different microbiota and different mice colonies on the development of the mucus layer and found no significant difference in proteins and goblets, but did find that the composition of intestinal microbiota has a major influence on the properties of inner colon mucus barrier. Another study found the similarity of the microbial ecology of monozygotic twins was higher than that for unrelated individuals, while those of marital partners where not (Zoetendal, 2015). This indicates that either early life environment or genetic background had a more predominant influence on microbiota than does current shared environment.

Overall, there are still many unknowns in the shaping of the microbiota, as also mentioned before, but this does indicate it is very much connected to the shaping of the mucus layer. The rate of secretion of mucus is regulated in an autocrine (feedback on itself) fashion by responding to pathogen triggers and environmental stimuli, immune response cells, endocrinal compounds and nervous stimuli. Both CD and UC have specific challenges in secretion of mucus. McGuckin provides more background information regarding the specifics of this. Overall, the mucus layer should be seen as an integrated component of innate and adaptive immunity that can be altered in terms of overall quantity and nature.

Practical takeaways regarding the mucus layer:

- Have patience and not do anything crazy: It was stated the whole intestinal barrier is regenerated completely every 7 months (NPO, 2019), and any form of detoxing of the bowel is completely unnecessary as the body does this continuously.

- Do genetic testing: If you are suffering from bowel diseases, it is good to know if you are genetically predisposed as this can help you with an action plan.

- Make sure I drink enough water and get enough nutrients.

2.3 The intestinal immune system

The intestinal immune system is a very flexible immune system with regional specialization, where antigens are sampled, processed and presented in such a way that enables the destruction of pathogens and tolerance of non-pathogens. Intestinal stability is maintained by 3 immunological barriers: first, immune mediators limit direct contact with bacteria and the epithelial surface, second; rapid detection and killing of bacteria that penetrate the mucus and third; minimize exposure of resident bacteria to immune system (Hooper, 2010). The mucus barrier serves a function with the first immunological barrier and without it inflammatory reactions are enhanced (Dotan, 2003). As a broad array of harmless compounds cross normal or damaged mucosal surface, it makes sense that the intestinal tract produces IgA instead of IgG, whose major effector function is antigen binding rather than the activation of an inflammatory response. Mucosal IgA is critical for the regulation of bacterial composition and represents the main element of the immune system involved in maintenance of gut flora homeostasis (Suzuki, 2003), where IgA has been found to be important in the formation of biofilms (Bolliger, 2003) and abnormal conditions can cause a significant shift in the anaerobic population in the small intestine. In IBD and celiac disease acute and chronic inflammation if characterized by a relative increase in IgG producing cell compared with IgA producing cells (Kagnoff, 1993).

In the second barrier communication can take place via cytokines, small molecular mediators secreted by macrophages. They are one of the compounds capable of activating an inflammatory response, and generally expressed in a suitable fashion for the environment that is designed to host the microbiota. However, they are produced more in individuals who experienced early life stress and conditions of both acute and chronic stress are also associated with higher levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Morey, 2015). Macrophages are also involved in the repair of epithelial cell damage, and this pathway can be activated by bacteria. There are various other ways in which the intestinal immune system is linked to the microbiota and the mucus layer, found in the expression of various compounds, lymphoid structures and regulatory mechanisms (Hooper, 2010). The specifics are largely still being investigated, and at the moment offer little practical value.

Practical takeaways regarding the immune system:

- I do not eat anything I am allergic to, as to not active the immune system of the gut with an inflammatory response.

- Stay in the comfort zone, do not spend energy you do not have as it is unnecessary stress and it will change the way the immune system responds

- Reduce physical stress:

- Stop intense exercising but keep moving. Walks not runs.

- Do not eat after 6 pm. As my digestion was off track I was experiencing a lot of pain. This was causing me to have trouble sleeping, and I was very tense while sleeping. I tried to limit the amount of digestion at night so I could rest

- Sleep more, as much as I need.

- Do not get hungry, keep my blood sugar leveled

- Reduce mental stress

- Turn my phone off more

- Take more time off

- Eat with company. It’s more fun and relaxing.

- Reduce physical stress:

3. Integration of the 3 pillars

People with ‘good’ genes, born from a healthy mother in a healthy environment will have grown up developing their microbiota and their intestinal mucus layer normally. They will bounce back quickly after an upset to their system. But there are a lot of influence factors on the development of poor digestive health:

- Birth. The method of birth and the period afterwards are suggested to have a large effect on the development of the microbiome and thereby the development of the immune system and the mucus layer. Specific information regarding the how is still debatable.

- Genes. There can be genetic predisposition for problems. The composition of the mucus layer can be compromised as well as the immune system.

- Experience (early life). frequent usage of antibiotics has been connected to problems with digestion later on in life.

- Daily diet. If your daily diet is that of a westerner in a city, it is most likely not supportive of good digestive health as its too low in complex sugars/fibers and too much fat.

And poor digestive health can lead to consecutive health problems. Once either one of the 3 pillars for a well-functioning barrier is compromised, the others are threatened as well. If the other two are also a bit poor, it is possible you enter a negative spiral. Once the barrier is compromised your overall health will start to decline. There are hypotheses that digestive health is connected to general health issues, mental health, autism and auto-immune diseases through the gut-brain barrier and due to the relationship with the central nervous system and the endocrine system. There is a nice Ted talk about the subject called Food for Thought. For me this made it very difficult to separate cause and effect. To be on the safe side I did additional blood testing for various hormones and immune related compounds as well as elaborate and repeated chemistry and genetic testing.

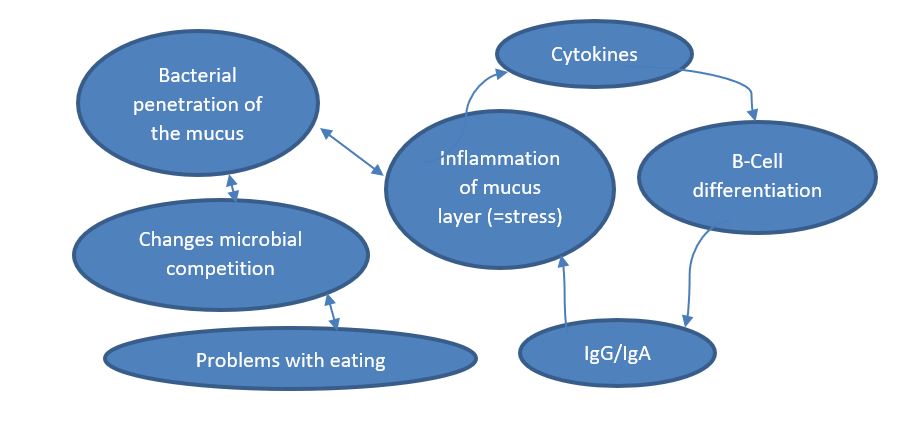

Through these conditions you could be in a negative spiral, which, simplistically, can look like the figure below. The intestine is in a state of stress or inflammation, therefore it releases specific cytokines. These cytokines determine the B-cell differentiation, which determines which antibodies are dominant. Under these conditions IgG is dominant over IgA, when IgG responds to a threat (allergy/microbial invasion) it responds with an inflammatory reaction (swelling, redness, stress hormones). Because your mucus layer now experiences inflammatory immune activity the mucus can be compromised, allowing penetration of bacteria. The penetration of the bacteria stimulates the immune system to respond as well, providing continuous conditions for inflammation and stress. As the microbes can also feed on the mucus, the ones penetrated in the mucus layer can have a competitive advantage over other bacteria and thereby determine the microbial ecosystem.

How to improve digestive health

There is only so much you can do. You can’t change your genes (yet, or affordably) and you can’t change your life experiences. But you can have an influence on anything you do from now on, so you can change the conditions from harmful to healing. Give the mucus-immune system and microbiome time to recover and gain strength like you would an open wound that needs to heal. Hold these restricted conditions and do not push your boundaries for a longer time (estimated 6 months – 2 years). I am not sure yet how to test how much time is enough. Maybe you will recover completely, maybe you will always have limitations. The practical tips I wrote at each part are the conditions I found and think will be helpful. These are possibilities and not complete, and I still have many questions regarding the microbiota specifically. I am also working on oral tolerance as an approach to combat allergies. I expect more scientific news on these fronts in the coming decade. So far, these conditions have helped me a lot in pain reduction, more freedom in my diet, more energy and better overall health.

Closing words

Illness is very complicated and different for everyone, but health is much simpler. So try to understand and approach health. I think I would not have been doing so well if I had not tried to focus on all 3 aspects of intestinal health: the microbiome, the mucus barrier and the immune system. I hope you have found this information useful in your own pursuit of health and understanding. I wish you all the best.

Natasja

References:

Bolliger. (2003). Human secretory immunoglobulin A may contribute to biofilm formation in the gut.

Cone, R. (2008). Barrier properties of mucus.

Corazziari. (2009). Intestinal mucus barrier in normal and inflamed colon.

Dotan, I. (2003). Intestinal immunity.

Egorov, V. I. (2002). Mechanical properties of the human gastrointestinal tract.

Goyal, R. K. (1971). Mechanical properties of the esophageal wall.

Hooper, L. (2010). Immune adaptions that maintain homeostasis with intestinal microbiota.

Jakobsson. (2014). The composition of the gut microbia shapes the colon mucus barrier.

Johansson. (2014). Bacteria penetrate the normally impenetrable inner colon muscus layer in both murine colitis models and patients with elcerative colitis.

Kagnoff. (1993). Immunology of the intestinal tract.

Kellow, J. (1995). Gut motility: in health and Irritatable bowel syndrome.

MacFarlane. (1997). Consequences of Biofilm and Sessile Growth in the Large Intestine.

McGuckin. (2009). Intestinal barrier dysfunction in IBD.

Morey. (2015). Current direction in stress and human immune function.

NPO. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.npostart.nl/dokters-van-morgen/22-01-2019/AT_2114965

Probert. (2002). Bacterial Biofilms In The Human Gastrointestinal Tract.

Schultsz. (1999). The intestinal mucus layer from patients with IBD harbors high numbers of bacteria compared with controls.

Sonnenburg. (2004). getting a grip on things: how do communities of bacterial symbionts become established in our intestine?

Suzuki. (2003). Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA deficient gut.

Zoetendal. (2015). Molecular Microbial Ecology of the Gastrointestinal Tract: From Phylogeny to Function.